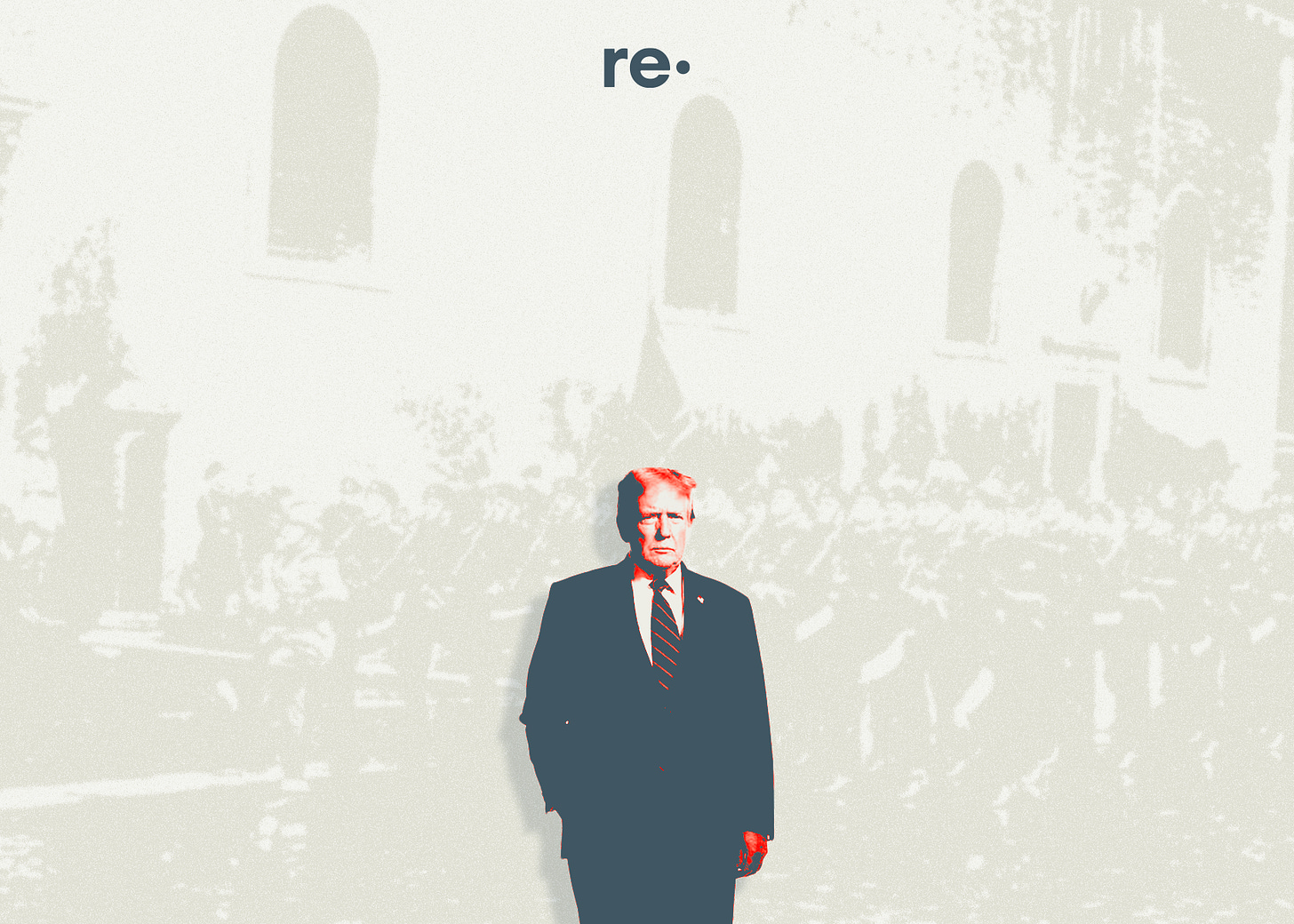

It has been an anxious start to the year to say the least. Devastating fires, the inauguration of a felon, an impending right-wing government in Canada – and somehow we are meant to continue fighting for change while keeping on top of our daily lives. It’s a lot.

None of this comes out of the blue. We are living in the world that many writers predicted would come to pass within our lifetimes (although their warnings went unheeded). Carl Sagan, in his 1995 book The Demon-Haunted World, described our contemporary reality with eerie clarity:

“I have a foreboding of an America in my children's or grandchildren's time —when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what's true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness…”

This prophetic quote speaks to why everything feels so overwhelming right now. We have lost the ability to even know or understand what’s happening in the world, because the control of information has been seized from us.

Now that we have entered this dark time, it’s hard to know what would be helpful to contribute amidst the deluge of information we are bombarded with. But it’s important to think through how we want to approach this precarious moment so that we may find clarity and strength to move forward without tuning out. Here are some of our ideas. We’d love to hear yours in the comments.

1. Attention is Power

The digital media environment is exhausting. Our attention is being pulled in endless directions, and it feels like a moral imperative to be on top of all of it. Being uninformed feels like a kind of failure. But it’s important to remember that attention has become a commodity in and of itself. Being able to command attention is a form of power that confers wealth, and gives a handful of individuals the ability to unilaterally reshape society.

Right-wing operatives are skilled at exploiting the voyeuristic nature of human attention. In his book Under the Cover of Chaos: Trump and the Battle for the American Right, Lawrence Grossberg describes how the alt-right uses an intentional strategy to pollute the media with chaos and noise in order to take up space and deflect attention from their real covert agenda. Elon Musk’s obviously fascist hand gesture at Trump’s inauguration is an obvious example. He knew what he was doing, and he knew that he would deny it publicly, and that it would cause a firestorm among liberals - to the delight of his supporters. This game of baiting, or ‘owning the libs’, where the entire internet convulses in useless debates about different versions of reality, is a game we don’t actually have to play. It sounds counterintuitive, but resisting the urge to pay attention to this kind of clickbait – especially provocative messages tailor-made to stoke outrage – is an act of resistance in and of itself. Focused, deep attention is powerful. Scattered, frantic attention is not.

In a recent podcast with Ezra Klein and Chris Hayes, author of The Sirens’ Call: How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource, Hayes likened the shift we’re undergoing now as comparable to the commodification of labour during the Industrial Revolution. Human beings underwent a shift from work that was connected to survival – farming, cooking, building – to factory labour that was divided into standardized units of time in order to be bought and sold. In order to support endless growth, capitalism must always find new frontiers. In the early modern period, this required the commodification of the body. Now, we have entered the era of commodification of the mind.

The rise of the Internet and the transition to the “knowledge economy” was supposed to be liberatory - a digital utopia of instant connectivity and global prosperity. But the reality didn’t turn out that way.

A key difference between industrial capitalism and the system we live in now – something that has been called surveillance capitalism or cognitive capitalism – is that, in the words of Italian philosopher Franco Berardi, “capital no longer recruits people, but buys packets of time.” In the computerization of society, human beings are no longer labourers in the traditional sense, but something more ephemeral: discrete cells of depersonalized time. Our attention becomes bought and sold without our knowledge or consent, and we dissolve into the thin air of cyberspace. As a result, according to Berardi, “workers no longer exist.”

In a world where we do not have the ability to control the flow of information, a handful of oligarchs will always be able to weaponize algorithms to shape society according to their private designs. This is the simple reason why Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg are effectively able to hand-select the president of the United States and dictate his behaviour.

This kind of power imbalance is not new. Technological innovation often proceeds in this way - new technologies are invented and monopolized by a small cartel of industrialists, until social and political movements force them to surrender power and democratize access to these resources.

In 19th century America, men like John D. Rockefeller or Andrew Carnegie were able to amass immense riches by creating monopolies (then called “trusts”) which controlled railways, energy production, and steel manufacturing. Virtually the entire economy fell under the control of these “robber barons.” It was only democratically elected governments that had the power to break up these trusts - and this was not possible without political agitation on the part of disenfranchised workers who were sick of exploitation and injustice. This was called the “Gilded Age,” a time in which inequality reached epic proportions–and researchers have shown that our levels of inequality are rivaling that of the Gilded Age once again. History shows that this level of social stratification is untenable in the long-term, but it doesn’t disappear without conscious struggle.

But if it is true that the commodification of attention in the 21st century mirrors the commodification of labour in the 19th century, then this offers lessons for our collective future. In his book Clear Bright Future, Paul Mason argues that we, as users of networks, must undergo “a process similar to that experienced by the working class in the 19th century.” In other words, “we need the ‘networked individual’ to change to an identity consciously crafted by collective action.” As users of networks, we must self-organize to control the access to information if we are ever to reclaim control of our social worlds.

Feminist scholar Silvia Federici expressed it well in this short video for the People’s Forum. She explains that we must be careful of the allure of social media, as it’s easy to believe that it’s bringing us together and helping us make progress, but in reality the forces behind it represent the zenith of unaccountable power. They’re able to control what we see, pay attention to, and how we are able to connect with one another. Social media gives us the illusion of democratization of information, when it’s actually controlled by the profit-maximizing algorithms of the most powerful people in the world. As Berardi puts it, “connectivity and precariousness are two sides of the same coin.”

There is a different kind of wealth, she argues, one that we ought to begin paying closer attention to. It’s the social wealth that arises when we come together to create a stronger communal fabric with those we are working and living alongside. This is our real source of power. She also cautions against the delusion that just because we can easily read about something going on in a faraway place doesn’t mean we actually know anything about those places. We must resist the temptation to try to know everything about everything. It’s impossible. And it can be liberating to stop trying.

Instead, we must zero in on what is most important for us to pay attention to – whether it be local politics in our neighborhood, mutual aid efforts in our region, or an issue of particular to our country. If we care deeply about housing affordability or women’s right to healthcare, we can seek out information to really understand what’s being proposed by local candidates, what advocacy organizations are asking for, and become a beacon of grounded information for that issue rather than forcing ourselves to comment on all of the latest headlines.

We can’t surrender to their clickbaiting and info-warfare. Let’s reclaim control of our attention, and get to work.

2. We’ve Been Here Before and the Pendulum Will Swing Again

The second thing we are thinking about is the fact that, as “unprecedented” as things might feel, we have unfortunately been here before. History might not repeat, but it does rhyme, as Mark Twain once said. There are some who have even tried to describe these patterns in cyclical terms, which is a useful framework for thinking about where we are today.

Karl Polanyi, one of the greatest economic historians of all time, explained in his influential book The Great Transformation that the Great Depression of 1929 was due to the triumph of unregulated capitalism and laissez-faire economic policies during the latter half of the 19th century. Clear analogies can be made to our own time, given the role that deregulation, privatization, and austerity have played in reshaping our societies since the 1970s. But if the 20th century is any indication, we have reasons to be concerned.

According to Polanyi, capitalist societies experience what he called a “double movement”: fluctuating periods of market liberalization and then self-correction, in which economic inequality gives rise to social antagonisms which necessarily produce demands to re-embed markets within the rules and regulations of nation-states. The outcomes of this process can be positive (i.e. the resurgence of social democracy and the welfare state), but also deeply negative (i.e. the rise of trade wars, reactionary movements, and even global conflict). Our own “double movement” will certainly contain elements of both.

But at the present moment, it seems like the negative aspects – the forces of destruction, tribalism, and isolationism – are winning. There are structural reasons for this. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, political theorist Hannah Arendt explained how the rise of global financial capitalism in the 19th century was implicated in the rise of fascism at the turn of the 20th century.

“[Arendt] laid particular stress on the fact that Europe’s nation-states had in a sense been transcended by the globalized industrial and financial capitalism that they had helped to create. Given the planetary scale and unprecedented transnational scope of trade, capital accumulation, and industrial growth, states were no longer able to control and regulate economic forces or their social consequences.” (Thomas Piketty, Capital and Ideology)

In other words, European societies destroyed themselves because a period of intense financial globalization and wealth concentration ultimately led to the disintegration of nation-states, the rise of racist ideologies, and inter-imperial rivalry culminating in World War I and then the rise of authoritarianism. In Arendt’s words, “the disintegration of the nation-state… proved to contain nearly all the elements necessary for the subsequent rise of totalitarian movements and governments.” The great tragedy of our own time is that history is repeating itself with an almost exact cadence. And it is not clear that we have learned any lessons.

There were many who predicted all of this. In the 1990s, when the dissolution of the USSR led to claims about the “end of history,” writers like Allan Bloom warned that “fascism has a future, if not the future.” And in their 1994 book called Data Trash: The Theory of Virtual Class, Arthur Kroker and Michael A. Weinstein predicted that the rise of the Internet and virtual reality would one day lead to a violent resurgence of fascism in an aggressive rejection of techno-globalism and digital hyper-capitalism. But these warnings fell on deaf ears.

We know that the results of this shift will be ugly. They will cause a lot of suffering. Freedoms will be curtailed, social safety nets will weaken, the commons will shrink. But in time people will realize that these policies have not delivered on their promises, and the pendulum will swing once again.

Resourcing and Refocusing

It’s important to remember that the moment that we are in resists a singular story. We are not doomed or heading straight for the apocalypse, but things aren’t going to be fine either. We are headed into a storm where there will be wins, losses, progress, setbacks, and many different combinations of all of them depending on where we live and what we are paying attention to.

There will be major losses, and there will also be many instances of people coming together to do things differently and take care of one another. All are true at the same time. There are reasons to despair and there are reasons to keep going. Keeping a balanced outlook and resisting the temptation of a simple, singular narrative is hugely important. Remind yourself that it is everything, all at once.

The question for us to consider is how we will lay the groundwork for what comes next. Progressive movements around the world are in the moment of rethinking that comes before rebirth. We must not stop thinking about what kind of society we want, and we cannot confuse the difficulty of achieving our aspirations with the impossibility of their realization. Do we want universal free child care, universal basic income, or student debt forgiveness? All of these take decades of campaigning, groundwork, and policy development before they can come to fruition. We must keep building, even when it is not our moment. Because it will be again.

The bottom line is this: take care of yourself, and take care of those around you. Pay attention only to what is truly important to you, and tune out the rest of the noise. And above all, keep going.

We’ll leave you with this quote from the great sociologist Zygmunt Bauman: “Humanity is in crisis, and there is no exit from that crisis other than the solidarity of other humans.”

What are you doing to keep sane in these times? Let us know in the comments below and stay tuned for our chat on this topic.

I agree that, given time, the pendulum will swing towards meeting the needs of the general population over the demands of the rich. Humans have always struggled with the abuse of power. There have always been rises and falls of power and fortune.

However, I don't think we have the time, let's say 10-20 years, to rectify and solidify a system that will redistribute wealth and power in a way that works for everyone.

If changes are not made to an economic system that continues to exploit natural resources as if those resources are unlimited, those resources will be exhausted before the necessary political changes can be made.

I don't know if my perception of the many environmental crises we face are shared by the majority of people. I don't know if there are enough people willing and ABLE to change the way they live to make a difference and stop the damage.

I am at the end of my life. If the difficulties were simply political and economic, I could let it go, knowing humans ultimately stand up for themselves and push back to create a better government.

It's the overwhelming loss of non-human life that grieves me. It's the fear and belief that much more will be lost before people are able and willing to change the way they live.